Cause area explorations: Human trafficking

This post is based on the recent human trafficking cause area investigation report I wrote for Christians for Impact. I’m still working on incorporating some expert feedback, so it’s likely there will be some additions to the report in the near future.

Why investigate human trafficking? Human trafficking or modern slavery is a popular cause area—not within the EA movement, but in the general population. This is especially so among Christians and even more among US Evangelicals. So, it seemed useful to investigate human trafficking to see how impactful anti-trafficking work is and what the best interventions are. Identifying the most effective ways to work on the problem is useful regardless of how anti-trafficking ranks compared to other cause areas, because there are many people who will want to work on human trafficking nevertheless. There are likely many such people among Christians, especially Christian do-gooder types, so it seemed useful for Christians for Impact to have an impact-focused report on human trafficking.

To my knowledge, no thorough EA cause-area investigation exists on this topic. There is a shallow investigation by Giving What We Can from 2016 and some EA Forum discussion. I’ve also seen it mentioned that Founders Pledge would have conducted some research on this topic, but if they did, they haven’t published it—they have a report on Violence against women and girls, but it only mentions trafficking in passing. The most significant EA-adjacent research effort in this space appears to be the Human Trafficking Research Initiative run by Innovations for Poverty Action.

At its current state, the CFI report does not fill the need for an in-depth cause area exploration report, but it provides some basic information, especially for a Christian audience, and can serve as a catalyst for personal exploration or further research with more depth.

What is human trafficking?

Definitions

There are at least two different ways to define human trafficking. I call these the narrow definition and broad definition. I’ll use the broad definition in this piece unless otherwise noted.

The narrow definition is something like (this particular wording is from Encyclopedia Britannica):

a form of modern-day slavery involving the illegal transport of individuals by force or deception for the purpose of labor, sexual exploitation, or activities in which others benefit financially

The key distinctive part is “involving illegal transport of individuals.”

The broad definition doesn’t require illegal transport. Under the broad definition, human trafficking is almost or entirely synonymous with modern slavery. Defined this way, the “trafficking” part is a bit of a misnomer. The broad definition seems to be the more common one and is used by the UN. The UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) defines human trafficking using a three-part act-means-purpose framework, where the trafficker must

recruit, transport, transfer, harbour or receive people (act)

using threats, force, abduction, false promises, etc. (means)

in order to exploit them (purpose).

The US government uses a similar three-part definition that doesn’t require transport, so you’ll encounter the broad definition in official US federal materials, too.

One more thing about definitions. Modern slavery is divided into forced labour and forced marriage.

How trafficked people are exploited

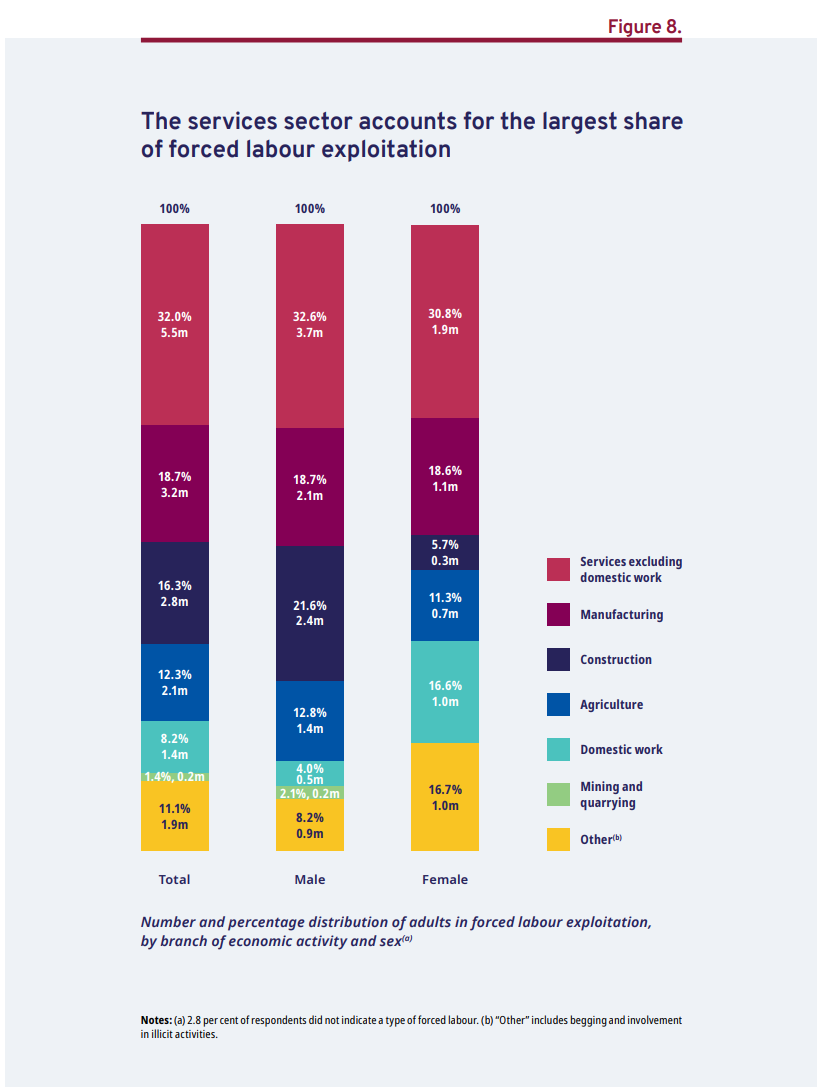

In popular imagination, human trafficking is often synonymous with forced sex work. This is a big part of the phenomenon, but most people in forced labour are exploited in some other way. According to the estimate of ILO, Walk Free and IOM, there are 6.3M people in “situations of forced commercial sexual exploitation” so roughly 20% of the 28M total in modern slavery (not including those in forced marriages). The graph below shows the sectors where adults in forced labour are exploited, excluding forced commercial sexual exploitation.

There is huge variation in trafficking situations. Trafficked people work in brick kilns in South Asia, logging in Brazil, fishing at lake Volta, cacao plantations in Ghana, fisheries in Southeast Asia, agricultural workers in the US, etc. Some do service jobs, others endure forced prostitutions, some work in internet scam factories, and others are forced to beg or sell wares on the streets. Making generalisations is difficult given the wide variety of circumstances. A related problem is that only a small fraction of human trafficking is detected—I’ve tried to be careful to distinguish between data based on detected cases and estimates of global prevalence.

Who are the trafficked people

The ILO, Walk Free, and IOM estimate that 57% of people in forced labour are male and 43% female. Including forced marriages changes the ratio but maybe not quite as much as you’d think: 46% of people in modern slavery are male when forced marriage is counted. Children make up 12% of people in forced labour without including forced marriages.

As you would expect, poverty and other adverse socioeconomic circumstances make people more vulnerable to trafficking. Still, it is not only people in abject poverty who are trafficked; 40% of victims have higher education. Trafficked people also come quite evenly from different income groups in their countries, as the stitched-together graphic from the ILO, WF and IOM report shows. The numbers represent thousands of people in modern slavery from each income group, so the High income number means 5,384,000 people and so on. The total adds up to 27,576,000 people.

Adapted (i.e., an MS Paint copypaste job) from the ILO, Walk Free and IOM report, page 17

Human trafficking perpetrators are sometimes stereotypically depicted as kidnappers unknown to the stranger. Abductions do happen, but only 3% of trafficked persons enter their situation this way. Many trafficking survivors have been trafficked by their romantic partners, spouses, parents, or other family members, or even their pastors. Fraud, threats or coercion are typical tools of control.

For human trafficking in the narrow sense, traffickers often seek people willing to migrate and promise them work or opportunities for work. The traffickers may supply fake travel documents to the victims. Passports and other documents are confiscated by the traffickers once the victims arrive at their destination. Victims are then often abused physically or sexually and forced into labour or sex work. False or deceptive contracts may be used to justify forced slavery. Traffickers use threats of deportation, seizing the victims’ travel documentation, or violence against their family members in the origin country as means of control. (Source)

ITN framework analysis

An EA cause area exploration would be woefully incomplete without and ITN analysis. The ITN framework (from Importance, Tractability, and Neglectedness) is a popular tool in EA for comparing cause areas. It has received its fair share of criticism over the years, but continues to be useful, especially for quick investigations and when used with due caution.

Importance

Human trafficking seems to score quite high on Importance (also called Scale). Various sources estimate that 27 or 28 million people live in forced labour, with the total number of people in modern-day slavery rising to a total 50 million if forced marriage is included. This is about the same as the number of HIV positive people in the world. Trafficking is also a huge business: ILO estimates a total of $236 billion in annual profits from human trafficking.

Human trafficking is obviously really bad for the victims. It can greatly harm their mental, physical, and sexual health, and it hurts the victims economically, socially, and spiritually. Trafficked people often experience (sources, more details and prevalence info in the report):

physical and sexual abuse

exhausting and hazardous work conditions

injuries, and diseases (especially STDs in sexual trafficking)

restriction of movement and inadequate access to health care

mental health issues like PTSD, anxiety, and depression

social isolation

experience shame about being trafficked and things they are forced to do

withholding of wages or not being paid in time

The GWWC report from 2016 had a tentative DALY (disability adjusted life years) estimate of 0.3–0.7. For comparison, acute low back pain with leg pain has a disability weight of 0.322, a moderate episode of major depressive disorder 0.406, and severe multiple sclerosis 0.707. At first pass, this seems plausible: being in slavery or slavery-like conditions seems very bad in itself, research associates modern slavery with serious mental and physical health problems, and being trafficked can greatly hurt people’s socioeconomic standing. I have questions about applying a measure for health conditions to something like slavery, though—perhaps WELLBYs (well-being adjusted life years) might be a better metric than DALYs in this case. The WELLBY-burden of modern slavery is likely significant and I would guess it could be comparable with a severe disease, but there is obviously a huge amount of variation in trafficked people’s experiences globally.

Neglectedness

Anti-trafficking efforts receive a lot of financial support and attention. International organisations like the UN, ILO and Interpol work on human trafficking, there are a plethora of anti-trafficking NGOs, and various state governments fund anti-trafficking efforts for hundreds of millions of US dollars per year.1 Most countries have signed the UN anti-trafficking protocol and have anti-trafficking legislation, though there is great variation in how the legislation is enforced.

This is more subjective, but human trafficking seems to receive a decent amount of media representation as well. This attention may sometimes be counterproductive to effectively solving the problem, though, as the media depictions can be inaccurate and even potentially harmful.

However, current efforts have been insufficient to eradicate the problem, and human trafficking continues on a large scale. The global annual funding of all anti-trafficking efforts is very likely under one per cent of the estimated $236 billion annual profits of human trafficking.

Tractability

Tractability is where things get difficult. The preceding facts about modern slavery are easy to document and mostly uncontroversial. But when it comes to cost-effectiveness of anti-trafficking interventions, there is a dearth of strong evidence. Many assessments and reviews of anti-trafficking interventions note this. The situation seems to have started improving in the latter part of the 2010s, but there is currently still insufficient evidence to determine which interventions work the best and how much they achieve per dollar spent. Below I identify some promising ones and ones that don’t seem to work well.

The Innovations for Poverty Action Human Trafficking Research Initiative is a promising project that attempts to tackle the current lack of evidence on what programs work to reduce trafficking and support victims. Another organisation that was mentioned as trying to fill the evidence gap by an expert we asked for feedback is HEAL Trafficking.

Here are preliminary findings on some intervention types (again, more details in the report):

Raising awareness: There is mixed evidence for different types of programs. Information and awareness-raising campaigns may improve knowledge, but generally they seem to have limited effects on actually reducing human trafficking. Some types of awareness-raising campaigns may have harmful results, but there may still be specific types of information and awareness-raising campaigns that work. There’s evidence that increasing the availability of information on worker conditions in factories and employing a fair recruitment program may lead to improved working conditions and reduced exploitation.

Advocacy and legislation: Many countries have anti-trafficking legislation, but existing legislation is often weak. Advocating for strengthening the UK Modern Slavery Act and similar existing legislation in other countries by adding sanctions and other enforcement mechanisms could be effective. However, I wasn’t able to find strong evidence about the results of this approach, though you can’t really have RCTs in something like this. HT Legal Center is an organisation working in this are mentioned in the expert feedback we received.

Economic empowerment programmes: Innovations for Poverty Action has identified economic empowerment programs as promising interventions to combat human trafficking, but by 2023, the highest-quality evidence on the effect of these programs on trafficking rates was lacking. These interventions are aimed at helping populations at risk of trafficking to develop livelihoods. This makes them economically more secure and less vulnerable to trafficking. These programs are also interesting because they would have other positive effects besides reducing trafficking, and in some cases reduced trafficking might even be an unintended bonus effect of a program focused on other goals

Trauma-informed mental health support for trafficking survivors appears successful at least in children, but there is much more limited evidence on mental health support in adult survivors. My naive guess is that this is much less cost-effective than interventions focused on prevention. The Human Trafficking Research Initiative of Innovations for Poverty A2ction identified this as a promising approach. Mental health was another area flagged in the expert feedback, so there might be more evidence or evidence for other interventions that I haven’t come across yet in this space.

Law enforcement and judicial capacity building is identified as a promising intervention by Innovations for Poverty Action, but they only reference one study to support this. In addition, International Justice Mission has reported promising results from their Program to Combat Sex Trafficking of Children in the Philippines in 2003–2015, and law enforcement and judicial capacity building are integral components of their model.

Freedom Fund’s hotspot model

In addition to these, there are big-if-true results from evaluations of Freedom Fund’s hotspot model. I wrote so much about this one that it deserves its own subheading. There’s some precedent for considering Freedom Fund: they have been discussed in the GWWC report and on the EA Forum as a potentially highly effective organisation.

Freedom Fund’s hotspot model includes funding a portfolio of grassroots organisations in areas that are considered human trafficking hotspots and "employing staff on the ground to support grantee partners and encourage the sharing of best practices."

Two independent evaluations (here and here, Freedom Fund’s own paper based on them here) reported strong effects in Indian hotspots, but they had no control groups and therefore don’t fulfil the criteria for highest quality evidence. The following numbers are from these three sources.

According to the evaluations, $15,800,000 was invested in 40 Indian frontline NGOs in two human trafficking hotspots in North and South India. Bonded labour fell from 56% of households to just 11% (on average) between 2015 and 2018 in over 1,100 target villages. This equated to roughly 125,000 fewer people in bondage across the project areas. Bonded labour in children was reduced from ~12–13% of households to 1–3%.

Freedom Fund reports $52 per person affected for the Northern India hotspot and $49 per person for the Southern India hotspot. However, “person affected” is not exactly defined in their report. Using just the reduction in the number of people in bondage and the overall investment of $15.8M, we get about $126 per one person fewer in bondage.

To me, $126 for one fewer person in bonded labour sounds extraordinarily effective. However, as is the case with extraordinary results, regression to the mean in repeat studies would seem likely. The short timeframe also raises questions of long-term sustainability of the results. From a DALY/WELLBY comparison perspective, it would also be important to know the counterfactuals: how many years would the person have spent in bondage, and how much better their life is as a result of not being in bonded labour? You could tell various different stories that have quite different implications for the difference in DALYs/WELLBYs between the counterfactual and the realised scenario. (For example, assuming entering bonded labour permanently ruins someone’s otherwise okay life versus assuming bonded labour is a few years of hardship in a life that would have been very difficult even without it.) I would need to dig deeper into circumstances in the trafficking hotspots and the details of bonded labour and its effects in these contexts to be able to properly evaluate these claims.

Taken at face value, $126 per person spared from forced labour might potentially be competitive with top GiveWell charities. Back-of-the-envelope calculation: if one fewer person in bondage were the equivalent of giving them just one QALY/DALY, which seems like a plausible number, this would mean ~40 QALYs gained with $5000. But I want to emphasise again that this analysis would need a lot more rigour and research on my part, and that there are reasons to question the $126 per person spared figure at face value.

Christian perspectives

As I mentioned in the beginning, human trafficking is an especially popular cause among (some) Christians. I’m not going to get into the socio-political reasons—you can find many takes of various temperatures by Googling if you’re interested—but it’s easy to present a case against slavery by appealing to some well-known Christian theological and ethical principles. Viewing human beings as bearers of the image of God and endowed with free will by their Creator quite naturally raises questions about owning, buying, and selling them. Doing unto others as you would have them do unto you is hard to fit with enslaving them.

The hardest part in a theological examination of slavery is probably that the Bible doesn’t explicitly denounce it and that historically, Christians more or less just lived with the existence of slavery. Still, many Christians started to consider slavery wrong based on their faith over the history of the Church even when they lived in societies where slavery was normalised. Examples include St. Gregory of Nyssa from the fourth century and William Wilberforce and other Christian abolitionists from the 18th and 19th centuries. (Some of the earlier examples like Gregory of Nyssa have been questioned, however: some say they are more concerned about the moral effects of slavery on the slave owners rather than criticise slavery as an institution. I haven’t looked at the original texts, so can’t really comment on this.)

Even in the absence of a general Biblical condemnation of slavery, there are many relevant Bible passages. The New Testament speaks of the equal worth of all people, whether slave or free, perhaps most famously in Galatians 3:28: “There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither slave nor free, there is neither male nor female; for you are all one in Christ Jesus.” (NKJV) The first epistle to Timothy 1:10 condemns “andrapodistés”, variously translated as kidnappers, enslavers or slave traders. The Greek word refers to a person who unjustly reduces free people to slavery (or steals the slaves of others).

There are also Bible passages which are not about slavery but touch on practices that are part of modern human trafficking, such as wage theft. For example, the Law of Moses forbids withholding the wages of a day labourer, Jeremiah pronounces a woe on those who do not give workers their wages, and the epistle of James says the wages of labourers that are kept back by fraud cry out to God. (Leviticus 19:13 and Deuteronomy 24:14–15; Jeremiah 22:13, James 5:4). The Old Testament is also full of verses against oppression and injustice, especially against vulnerable people.

But ultimately, the most straightforward Christian argument against modern slavery is from love. The commandment to love one’s neighbour as oneself is incompatible with the cruel realities of human trafficking. There may be socio-political reasons for the popularity of human trafficking as a cause area among certain Christian groups, but I’m sure that for many Christians the reason they care is the visceral wrongness and injustice of human trafficking. Human trafficking also likely feels less inevitable and therefore more tractable (and more wrong) than something like malaria, since trafficking is something that’s actively perpetrated by the traffickers on other human beings.

But speaking of Christian perspectives on human trafficking, I must mention the various poor media depictions and stereotypes. These matter because they might significantly influence donations and Christian anti-trafficking work. There is a kind of genre of Christian human trafficking movies, some of which have very questionable messages. For example, the movie Sound of Freedom has been criticised for its portrayal of trafficking scenarios, simplifying complex issues, and showcasing tactics that might inadvertently increase demand for trafficked children. Christians should be aware of sensationalising tendencies and people exploiting the strong emotions the topic of human trafficking raises.

Conclusion

My investigation was not super thorough, so it is possible I may have overlooked some promising interventions, and the expert feedback we got points towards areas of further investigation. Based on my current understanding, one of the best things to do for people who want to have the biggest positive impact on human trafficking would be conducting high-quality research on the effectiveness of anti-trafficking interventions and possibly also helping organisations to conduct good impact measurement. The Human Trafficking Research Initiative by Innovations for Poverty Actions seems very promising. The University of Nottingham Rights Lab has also been recommended to us. Compiling and disseminating evidence on the effectiveness of various anti-trafficking interventions among Christian audiences seems valuable.

Another direction could be exploring promising, scalable solutions like those mentioned in the Innovations for Poverty Action 2023 Best Bets report, or ones that their Human Trafficking Research Initiative has identified (see section on tractability for more details on these interventions). These include but are not limited to the following:

Economic empowerment programs

Law enforcement and judicial capacity building

Increasing the availability of information on worker conditions in factories

Ethical recruitment models

Trauma-informed mental health support for former child soldiers

Educational interventions could improve healthcare and specialized social workers’ ability to identify and support human trafficking victims in the US, likely also in other countries

In the expert feedback we received, the work of HEAL Trafficking was recommended, and International Justice Mission also reports some impressive numbers from law enforcement and judicial capacity building in the Philippines, but I haven’t yet been able to dig deeper into the activities of these organisations. I expect that there will be other promising interventions added to the report as we continue receiving and processing feedback.

If you have additional ideas, thoughts or criticism about any of the points I made in the report or in this blog post, let me know! Thoughtful feedback is very welcome.